Lessons From Three Decades of Getting the Future Almost Right

Predicting the future of media is a strangely intimate act. It forces you to look at technology. It also makes you look at yourself—your assumptions, your blind spots, and the cultural air you breathe without noticing. I’ve been making these predictions for more than thirty years. It has been long enough to see some of them come true. Others have fallen apart. Many have landed somewhere in the ambiguous middle.

My earliest attempt came in 1991, when I was a PhD student at Michigan State. Cable television offered roughly twenty channels, and the idea of a hundred‑channel universe felt expansive, even radical. I imagined a world where this abundance would allow each of us to live inside our own entertainment bubbles. We would be free from the homogenizing effect of the three major networks. In a sense, I was right: we do live in fragmented media worlds. But I missed the deeper consequence—the way separate news ecosystems would harden political identities and accelerate polarization. I saw the technology; I didn’t yet see the sociology.

In 1998, I spoke at a media conference in Grand Forks. I predicted that the internet would soon replace local newspapers as the primary profit center for print media. That shift did happen, but not in the way I imagined. I underestimated the collapse of local advertising. I also underestimated the rise of platform intermediaries. Additionally, I did not foresee the difficulty newspapers would face in monetizing digital audiences. Once again, the destination was right, but the route was wrong.

In 2000, I contributed two chapters to Media 2025. In one, I argued that low‑Earth‑orbit satellites would become a major force in global communication. Starlink now orbits at roughly 340 miles. This proves the basic logic sound. However, I assumed these satellites would be used primarily for telephony. I did not expect their use for internet access. In the other chapter, I predicted the rise of “zero‑motion players”—solid‑state devices capable of storing vast libraries of music. For a time, that prediction was spot‑on. iPods and early smartphones embodied exactly that vision. However, what I didn’t foresee was the next leap. The shift moved from ownership to cloud‑based subscription services. This change has made local storage almost irrelevant.

Looking back, my errors fall into four categories. Sometimes I misunderstood the effect. Other times I misunderstood the method. In a few cases, I predicted the technology but not its primary use. And occasionally, I failed to anticipate how multiple technologies would interact to create something entirely new. Those lessons shape how I think about the next 25 years. I view them less as a straight line. I see them more as a set of overlapping trajectories. Each is influenced by economics, culture, regulation, and human behavior.

Today, artificial intelligence sits at the center of nearly every conversation about media’s future. Analysts at EY (2025) argue that AI is no longer a novelty. It has become a strategic priority. Executives are increasingly focused on operational integration. Over the next quarter‑century, AI will likely become the invisible backbone of content creation. It will power everything from automated newsrooms to hyper‑personalized entertainment streams. Entire franchises may emerge with AI‑generated actors, writers, and production teams. Costs will fall. Competition for attention will rise. The distinction between human‑made and machine‑made content will become a central cultural question.

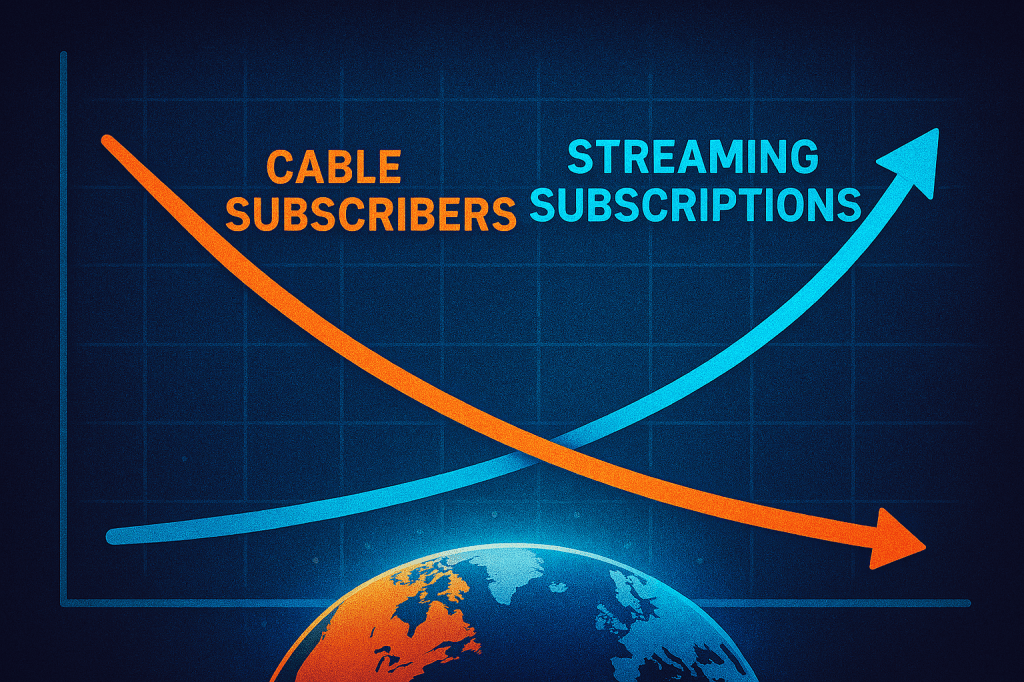

At the same time, the long decline of linear television will continue. Cable subscriptions have already dropped from 63% to 49% in just three years (Robino, 2025), and by 2050, the shift toward streaming will be complete. But streaming itself will not remain the fractured landscape we see today. Instead, Deloitte (2025) and EY (2025) both point toward consolidation. They forecast fewer platforms and larger bundles. There will be a return to aggregation. This time, global tech companies, rather than cable operators, will control it. Live sports and news may be the last bastions of linear formats. However, even they will eventually migrate into hybrid, interactive environments.

Advertising will dominate the economic model. Robino (2025) notes that digital advertising is projected to exceed 80% of total ad revenue by 2029, and that gap will only widen. Subscription fatigue is driving consumers toward ad-supported tiers. AI-driven targeting will make advertising more precise. It will become more contextual and more deeply embedded in immersive environments. The line between content and commerce will blur as AI will integrate content and advertising in a new wave of product placement. Products we might buy May become a part of the entertainment.

Immersive media—VR, AR, mixed reality—will mature unevenly but steadily. EY (2025) suggests that experiential entertainment is already gaining traction, and over the next decade, immersive formats will become as common as mobile video is today. Gaming will lead the way, merging with film, social media, and live events to create persistent story worlds. The “metaverse,” stripped of its early hype, will evolve into a practical layer of digital‑physical interaction. As devices transition from mobile to wearable (or implantable) we may communicate and be entertained in an environment invisible to others.

Creators will continue to reshape the power structure. Deloitte (2025) highlights the rise of creator‑led ecosystems. In these ecosystems, individuals build global brands. They are supported by decentralized monetization models. AI tools allow a single person to operate at studio scale. Traditional media companies will shift toward talent incubation. They will focus on intellectual‑property management. They will cede day‑to‑day production to a distributed network of creators and micro‑studios. In effect, rather than selecting content for audiences, transitional media companies will just manage payments or advertising content.

Globalization will accelerate as well. Mordor Intelligence (2025) identifies Asia‑Pacific as the fastest‑growing media region, and over the next 25 years, non‑Western markets will dominate global consumption. Cross‑border co‑productions will become standard, and localized content—linguistically, culturally, narratively—will be essential for global success. Distribution platforms will standardize rights and royalties, creating a more unified global marketplace. Smart translation systems will move from translating the audio from one language to another. The “actors” will appear to speak, even dress appropriately for each target culture.

Economic constraints matter too. Streaming markets are saturated, immersive hardware remains expensive, and advertising fatigue limits growth. Not every innovation is financially viable. Regulatory friction adds another layer of complexity. Concerns about misinformation, AI‑generated content, and platform power create political pressure for oversight, slowing the pace of change. And beneath all of this lies cultural stability. Media habits evolve far more slowly than technology. Many people still prefer curated news, linear formats, or human‑made content. Culture resists disruption even when technology enables it.

Taken together, these forces suggest that the next 25 years will not be a clean break from the past. Instead, it will be a negotiation. There will be a push and pull between innovation and inertia. Global platforms will clash with local identities. Automation will compete with human creativity. The past three decades have taught me one crucial lesson. The most interesting changes do not happen when a technology arrives. They occur when people decide what to do with it. The future of media will be shaped not only by AI, satellites, immersive worlds, or global platforms. It will also be influenced by the choices audiences make. The values they hold will play a significant role. Additionally, the trust they extend—or withhold—from the systems that mediate their lives will be crucial.

The question now is where have I gone wrong this time. Have I underestimated a technology, misunderstood a market, or failed to take technology integration into account? The future will tell.

References

Deloitte. (2025). Media and entertainment outlook. Deloitte.

EY. (2025). Five media and entertainment trends to watch in 2025. EY.

Mordor Intelligence. (2025). Media and entertainment market analysis: Growth trends and forecast (2026–2031). Mordor Intelligence.

Robino, C. (2025). Global media industry analysis 2025: Crucial trends. chrisrobino.com.

WARC. (2025). 2025 media trends & predictions. kantarmedia.com.